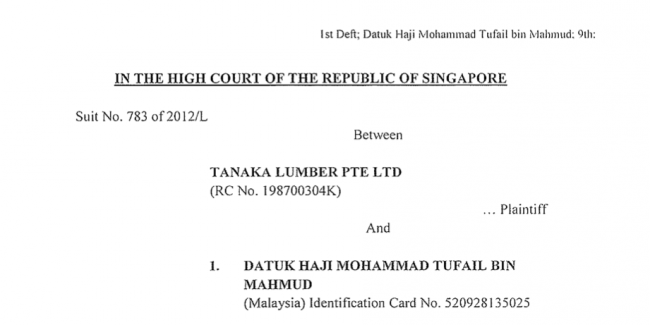

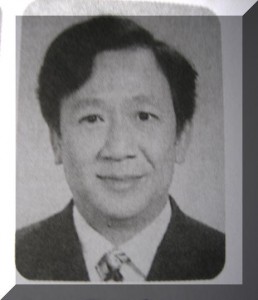

The brother of Governor Taib Mahmud, Tufail, is due to appear in a Singapore High Court today to be questioned in a case brought against him by former business associates.

However, papers already deposited before the session in Court 5 contain a series of astonishing admissions by Tufail, where he openly details how he illegally evaded paying tax on his timber profits made out of Sarawak.

The complex case, which opened earlier this month, was brought by a Singapore company called Tanaka, of which Tufail is himself a director, against both himself and a fellow director of Sanyan Sdn Bhd, Dato Ting Check Sii.

The majority of the three shareholders of Tanaka are suing to be paid back money, which they say was lent to Sanyan for ventures in Sarawak on the understanding it would be repaid.

However, the minority director Tufail, who now controls Sanyan and has evicted Ting from his former positions in the company, is refusing to comply.

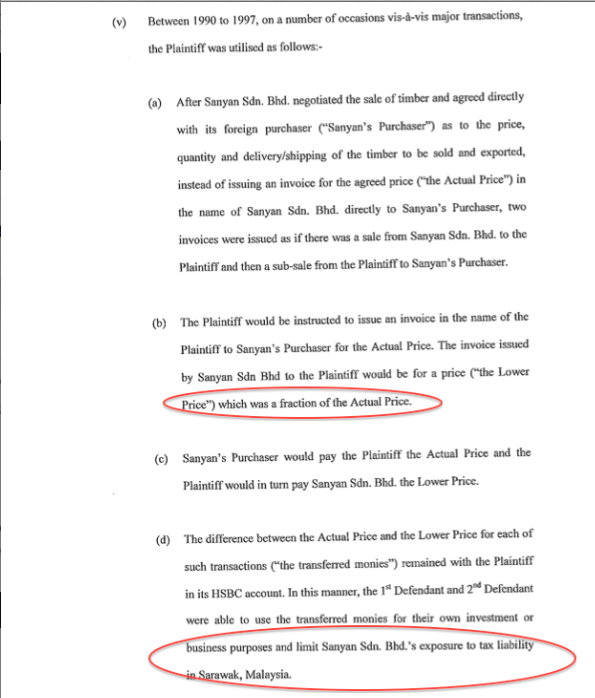

It was during his earlier, written submissions to the court over this dispute, that Tufail detailed how for many years he declared his sales on timber from the state at only a “fraction of the actual price” to the Malaysian tax authorities.

It means that the people of Sarawak were denied their rightful profits from this logging of state lands – concessions which had been granted to Tufail by his own brother the Chief Minister of the time

Tufail Mahmud’s tax dodging scams on Sarawak timber sales

Tufail’s tax-dodging scam, according to his own statement to the court, was to ‘sell’ the timber from his companies Sanyan Sdn Bhd and Sanyan Sawmill Sdn Bhd to a so-called ‘agent’ in Singapore, which in turn re-invoiced the end buyers in places like China and Japan for a much larger sum.

That ‘broker’, a company called Tanaka, turns out to have also been owned by himself and his business associates!

By this method (politely known as ‘transfer pricing’) Tufail and his fellow shareholders cheated the people of Sarawak out of tens of millions of ringgit of tax by hiding the extent of their real profits.

It is a practice that has been seen as commonplace for the major timber companies, who tend to habitually declare pathetic profits or even losses each year, even though Sarawak is still the largest tropical timber exporter in the world.

According to Turfail’s submissions, his bent business then used these secret profits to plough into other ventures in Sarawak, such as the Sanyan Tower in Sibu, in which they again enjoyed favoured status, thanks to the influence of Tufail’s brother Taib Mahmud.

This is how Tufail described what he was doing to the Singapore court:

The un-repentent admission is likely to provoke outrage from ordinary Sarawak folk, who have seen endless favours granted to Taib’s family, only to be cheated further by such meanness in evading tax.

‘Transfer pricing’ was the practice spelt out by Taib family lawyer Alvin Chong in Global Witness expose

This flagrant practice of transferring profits away from Sarawak, in order to avoid tax, was of course described as a standard manoeuvre for Taib family hangers-on by cousins of the Chief Minister, when they were secretly recorded during a separate Global Witness expose back in 2012.

They and their lawyer Alvin Chong are seen on video laughing and joking as they tell an investigative reporter that no one who is ‘connected’ in Sarawak seriously pays tax on the lands and favours they have grabbed, thanks to their relationship to Taib.

This is because they only receive a fraction of the actual price of land and products in Sarawak – the rest is paid offshore, in such places as Singapore.

The biggest victims of this tax evasion are of course the wider public, who are thereby deprived of funds for services like health and education.

In the Global Witness video the Mahmud cousins were not only caught discussing their scheme to evade taxies in this way (by selling on a cheap oil palm concession through Singapore) they chose to describe the native customary land owners of the territories concerned as “squatters”.

They also sneered at the local ‘nominees’ whom they had hired to disguise their shareholdings, calling them “one-eyed in a land of the blind” – a reference to ordinary folk, who do not realise how badly they are being robbed by the Taibs and others in power in the State of Sarawak.

Secret timber concession

The Singapore court case is one of several waged against Tufail by former business partners and these have revealed another disturbing deception by Taib’s brother.

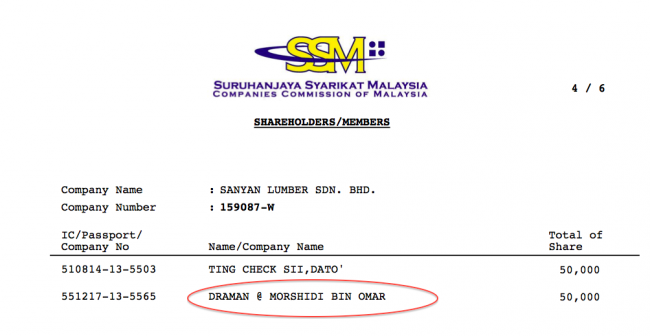

Tufail was also hiding his ownership of a lucrative timber concession granted by Taib, according to separate court papers. Sanyan Lumber Sdn Bhd was the name of the concession, which was the source of much of the money flowing through Tanaka Lumber in Singapore.

Tufail is not listed as a Director or Shareholder of the company, however, his partner Dato Ting Check Sii, has confirmed that he was indeed the 50% shareholder, which provided the key source of timber behind Sanyan’s exports:

“In 1987, I set up Sanyan Lumber Sdn Bhd which was given a timber concession. The shares of this company are held by me (50%) and Draman @ Morshidi bin Omar (50%) (as nominee of Datuk Tufail). Datuk Tufail told me that he needed to use a nominee because his brother was then and still is the Minister for Resource Planning. Datuk Tufail now denies Draman is his nominee, even though Datuk Tufail and I are the only joint bank signatories for this Company”. [Submission by Dato Ting to Sarawak High Court]

In other words Mr Bin Omar was merely a nominee, of the sort described by Alvin Chong as a one eyed man in the land of the blind (meaning the Dayak of Sarawak, who were allegedly unaware how they are habitually cheated in this way).

In fact, Ting’s submissions to the court make clear that Tufail’s primary role in the Sanyan business empire was to make sure it obtained favour in securing those vital timber concessions from his brother. Tufail never actually did any of the work in the company and he never invested any of his own money:

Tufail himself has admitted to the court in his own written submission for the current case that he barely did a thing towards running the business itself:

How much was Tufail fined?

There is one major gap in the otherwise shockingly frank evidence given in this case by Tufail about his tax dodging, which is how much he was fined after he got caught?

Taib’s brother admits in his evidence that in the late 90s the Malaysian finance authorities spotted what he was up to and proceeded against his company Sanyan.

The outcome was negotiated and the company was indeed fined for this illegal behaviour, according to Tufail’s own narrative.

But Mr Mahmud does not say by how much he was fined, leaving onlookers to speculate that Taib’s brother may have got off very lightly indeed.

After all, according to the court papers, Tanaka had secreted some USD$10million from under the noses of the Sarawak authorities by its false invoices and accounting and then re-invested it in the Sanyan Tower and other enterprises.

These enterprises remain in the hands of Tufail, so how much was he actually forced to pay back?

Don’t the public have a right to know if a settlement was reached that was below the amount he would have paid had he honestly declared his taxes? Under normal circumstances Sanyan ought to have paid a substantial fine of top of the taxes, after all.

Breech of promise along with tax dodging

Amongst the sorriest victims of Tufail’s activities have turned out to be his own former business partners, according to the submissions in this and other cases between him and fellow directors in Malaysia.

Those entrepreneurs, who needed to give a majority share of their business to a lazy Mahmud family member, in order to have a chance to get concessions and do business in Sarawak.

After their usefulness was over and the business was built, their submissions complain that Tufail squeezed them out like a cuckoo in their nest.

In this latest Singapore complaint Tufail stands accused in a complicated claim of a breech of trust for not having fulfilled an alleged commitment by Sanyan to pay back the money invested from Tanaka within 18 years (a period now expired).

But from the point of view of people in Sarawak, the real outrage is the way this case reveals, yet again, how the state has been corruptly managed by Taib Mahmud for the benefit of his own family businesses.

So far all the legal actions against Tufail have been lost in the Sarawak courts, perhaps unsurprisingly given the Taib family’s influence.

It remains to be seen whether the case in Singapore will obtain a long awaited victory for his discarded former business partners. It’s clear that even the winners in Taib’s Sarawak are in danger of becoming losers, unless they are part of the Taib family themselves.